[:en]Millarca Valenzuela, geologist and part of the Millennium Institute of Astrophysics MAS and the Centre for Astro-engineering UC (AIUC), leads CHACANA Project (Chilean Allsky Camera Network for Astro-geosciences,) which already has the first cameras that will work as a prototype to create a network that will allow the monitoring of meteors that enter the atmosphere and hit national territory.

The importance behind recovering meteorites just days after they hit ground is what drove Geologist Millarca Valenzuela, member of the Millennium Institute of Astrophysics MAS and Centre for Astro-engineering UC (AIUC,) to create the first meteorite follow-up and observation system in Chile. CHACANA (Chilean Allsky Camera Network for Astro-geosciences) was born from the interdisciplinary work between Millarca and astronomer Leonardo Vanzi from IAUC, along with the collaboration of Samuel Ropert, Vincent Suc and Andrés Jordán (also from MAS,) specialists from OBSTECH Company.

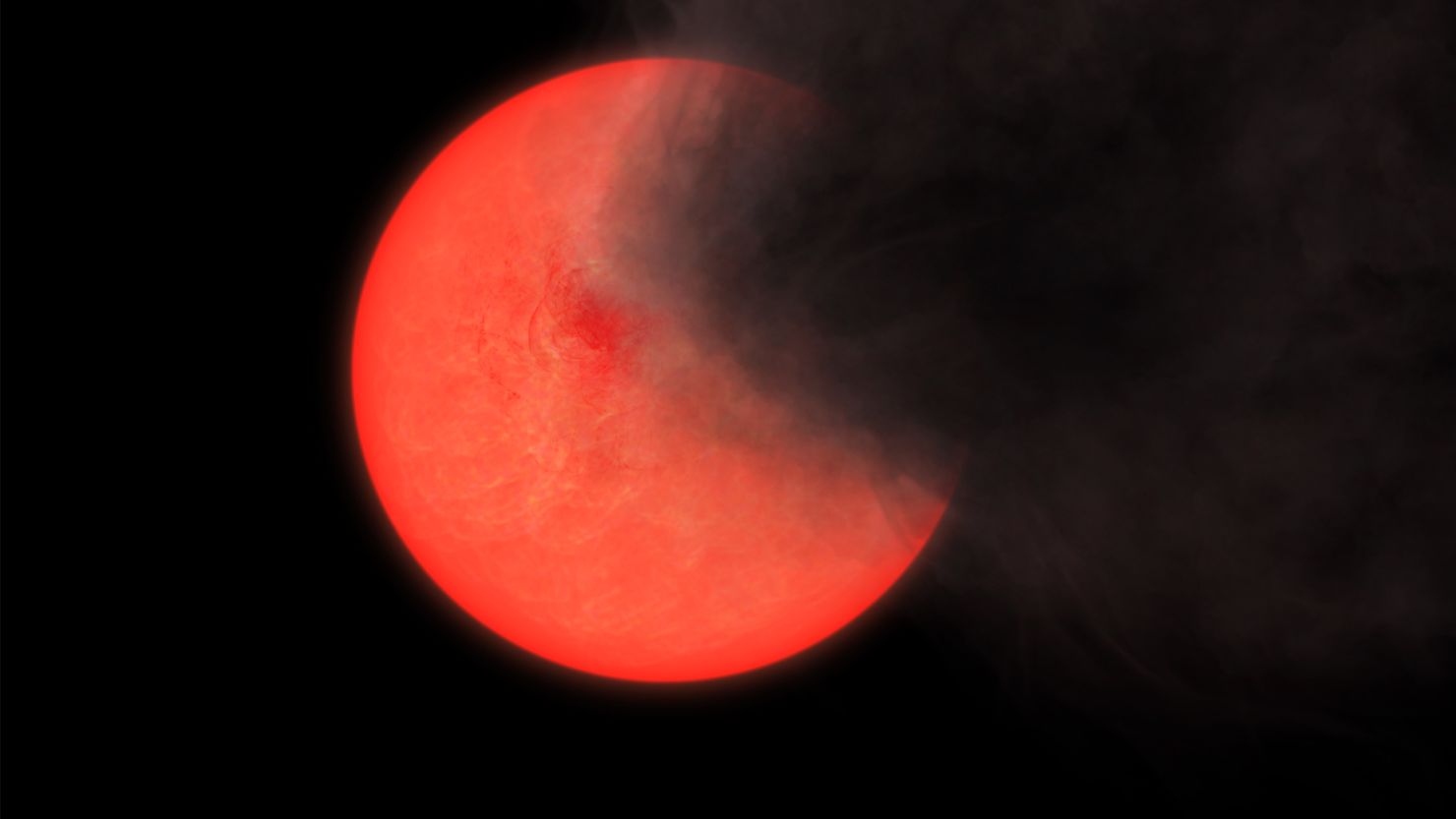

Camera network CHACANA, installed around 100 km. from each other, will detect when a meteor enter the atmosphere through an image discrimination software, and through triangulation with data obtained from proximate cameras it will be able to calculate both the object’s entry orbit –it corresponds to different asteroidal families that cross the Earth’s orbit– and the spot where that possible meteorite hit ground. This will allow the organization of an expedition to recover it and with that a more precise study of it.

“When a meteorite hits the Earth, the atmospheric oxidation starts immediately to affect the meteorite. The reaction with oxygen transforms its primary mineralogy into minerals more resistant to Earth conditions, mainly iron oxides. That is why we hit the jackpot, in a manner of speaking, when we instantly recover the meteorites that have just hit ground, since we can study processes that happened million years ago without the interference of these new Earth’s minerals,” Millarca explains.

To make the most of that opportunity is precisely what CHACANA aims to do. This network has two cameras for now, one located at El Sauce Observatory (IV Region) and the other one eventually at Las Campanas. However, according to Millarca in order to this network to work correctly they need to install about 20 cameras distributed throughout the country. “Chile is an ideal country to install this network, specially the desert. In Europe, there are a lot of these projects, but it’s hard to recover the meteorites. What they have in its place are large statistical databases about the material that comes into the atmosphere. Chile, instead, has the desert in the north, what means that if a meteorite hit ground there, it wouldn’t be easy for it to move, which makes our expedition easier. However, CHACANA’s main goal is not only install cameras in the north, but throughout Chile.”

Community Science

Even though CHACANA is still a prototype and currently is working on the meteor discrimination software –which has turned to be the biggest challenge on this project since it needs new sources of financing for its implementation– in the future it is expected to add different aspects to this camera network and even include the community to this project. “The location for each camera is not defined yet. However, I think it is essential to install them at schools, institutes, universities, etc., throughout Chile, that is, cameras connected from different places to a central office and from each other to provide data that can allow us to apply this software and have a combination of information to get a successful detection. I think is relevant to bring science closer to the community, make them feel part of what we’re doing and, in this way, foster young people and kids to study scientific and/or technological degrees,” the Geologist states.

In this sense, Chile’s latitude should not be an issue: “In Europe and every country where we can find these detection networks, cameras are located at even lower latitudes than Valdivia. This is not an obstacle, since what’s important in a meteorite is its brightness, which is so high that cloud cover doesn’t block its detection, to a certain limit.

What comes next

After the software implementation, the following step for CHACANA is starting to register events and gather information. According to Millarca, the first phase is increase statistical stacks of objects that enter to the Earth, from southern hemisphere. All this in order to complement other networks’ data, like the one in Australia, which is the only one –apart from CHACANA– in this part of the globe right now, unlike northern hemisphere where we can find several of these projects.

“We still have a long way to understand meteorites, that’s why it is so important to recover them right away. All we can learn from them will help us to understand more about planets formation, life’s origins and the nature of the material that can eventually collide with the Earth. There’s a large percentage of these objects that we don’t know yet and in order to carry out simulations we need to learn which kind of materials and densities are made from, along with more relevant information that will allow us to make models and to be a little bit more prepared,“ Millarca ends.

Image 1: Camera located at El Sauce Observatory

Image 2: Test image taken by CHACANA’s prototype camera AllSky at Gemini Observatory in September 2016, where we can observe a meteor at the top.[:es]El proyecto CHACANA (Chilean Allsky Camera Network for Astro-geosciences) es liderado por la geóloga del Instituto Milenio de Astrofísica MAS y del Centro de Astroingeniería UC (AIUC), Millarca Valenzuela, y ya cuenta con las primeras cámaras que funcionarán como prototipo para la creación de una red que permitirá el seguimiento de meteoros que entran a la atmósfera en todo el territorio nacional.

La importancia de recoger meteoritos a sólo días de su ingreso a la Tierra es lo que motivó a la geóloga Millarca Valenzuela, miembro del Instituto Milenio de Astrofísica MAS y del Centro de Astroingeniería UC (AIUC) a crear el primer sistema de seguimiento y observación de meteoros en Chile. CHACANA (Chilean Allsky Camera Network for Astro-geosciences) nace del trabajo interdisciplinario entre Millarca y el astrónomo Leonardo Vanzi, del AIUC, junto con la colaboración de Samuel Ropert, Vincent Suc y Andrés Jordán (también del MAS) especialistas de la empresa OBSTECH.

La red de cámaras CHACANA, instaladas aproximadamente a 100 km. unas de otras, mediante un software de discriminación de imágenes detectará cuando un meteoro entra en la atmósfera, y a través de una triangulación con los datos de cámaras aledañas podrá calcular tanto la órbita de entrada del objeto – correspondiente a diferentes familias de asteroides que cruzan la órbita de la Tierra – como el lugar donde el posible meteorito aterrizó. Ello permitirá organizar una expedición para recuperarlo y con ello estudiarlo con mucha mayor precisión.

“Cuando un meteorito cae a la Tierra, inmediatamente empieza a ser afectado por las condiciones oxidantes de la atmósfera. La reacción con el oxígeno transforma su mineralogía primaria en minerales más estables a las condiciones de la Tierra, principalmente óxidos de hierro. Es por eso que las joyas de la investigación de los meteoritos son justamente los que caen y se recogen de inmediato, porque podemos estudiar procesos que ocurrieron hace millones de años sin la interferencia de estos nuevos minerales terrestres”, explica Millarca.

Aprovechar eso es precisamente el objetivo de CHACANA, red que por ahora cuenta con dos cámaras, una ubicada en el Observatorio el Sauce (en la IV región) y otra eventualmente en Las Campanas. Sin embargo, según Millarca para que la red funcione de manera óptima se debe contar con unas 20 distribuidas en todo el territorio nacional. “Chile es un país ideal para instalar esta red, sobre todo el desierto. En Europa existen muchos de estos proyectos, pero es difícil recuperar el meteorito. Lo que ellos tienen son bases de datos muy grandes de estadísticas sobre el material que entra a la atmósfera. Chile en cambio tiene por el norte el desierto, lo que implica que si cae un meteorito ahí, es difícil que se mueva, lo que hace más fácil su búsqueda. Sin embargo, el objetivo final de CHACANA no es sólo instalar cámaras en el norte, sino en todo Chile”.

Ciencia ciudadana

Aunque CHACANA es aún un prototipo y actualmente se trabaja en el software de discriminación de meteoros – lo que se ha convertido en el mayor desafío del proyecto a causa de que necesita nuevos financiamientos para su implementación- en el futuro se espera que esta red de cámaras tenga variadas aristas e incluso se incluya a la ciudadanía en el proyecto. “La posición que tendrán las cámaras aún no está definida. No obstante, creo que sería fundamental instalarlas en colegios, institutos técnicos, universidades, etc., en todo el país. Que las cámaras se conecten desde estos lugares a una central y se alimenten unas a otras, generando datos que nos permitan aplicar el software y tener una combinación de información para una detección positiva. Creo relevante llevar la ciencia a la comunidad, que se sientan parte de lo que estamos haciendo y así incentivar a jóvenes estudiantes a seguir carreras en ciencia y/o tecnología”, argumenta la geóloga.

Esto no importando la latitud del país: “En Europa y en todos los países donde existen este tipo de redes de detección, las cámaras están ubicadas en latitudes menores que las de Valdivia incluso. Esto no es un impedimento, porque lo significativo de un meteoro es su brillo, que es tan alto que la cobertura de nubes no impide, hasta ciertos límites, su detección”

El trabajo que viene

Luego de la implementación del software, el siguiente paso para CHACANA es comenzar con el registro de eventos y recopilación de información. Según Millarca, la primera etapa es crecer en la acumulación de estadísticas de los objetos que entran a la Tierra, desde este punto del hemisferio sur. Eso para complementar los datos con otras redes, como la de Australia, la única – aparte de CHACANA – que existe en esta parte del mundo hasta el momento, a diferencia del hemisferio norte en que estos proyectos son numerosos.

“Aún nos falta mucho por entender acerca de los meteoritos, por eso es primordial recogerlos muy tempranamente. Todo lo que podamos aprender de ellos, nos ayuda a entender más sobre la formación de los planetas, el origen de la vida y sobre la naturaleza del material que eventualmente podría impactar a la Tierra. Hay un gran porcentaje de estos objetos que aún no conocemos y para hacer simulaciones necesitamos saber qué tipos de materiales y densidades tienen, junto con otra información relevante que nos permitirá hacer modelos y estar un poco mejor preparados”, concluye Millarca.

Imagen 1: Cámara ubicado en Observatorio El Sauce

Imagen 2: Imagen de prueba tomada por cámara AllSky prototipo proyecto CHACANA en observatorio Gemini en Septiembre 2016, donde se observa un meteoro en la parte superior.[:]